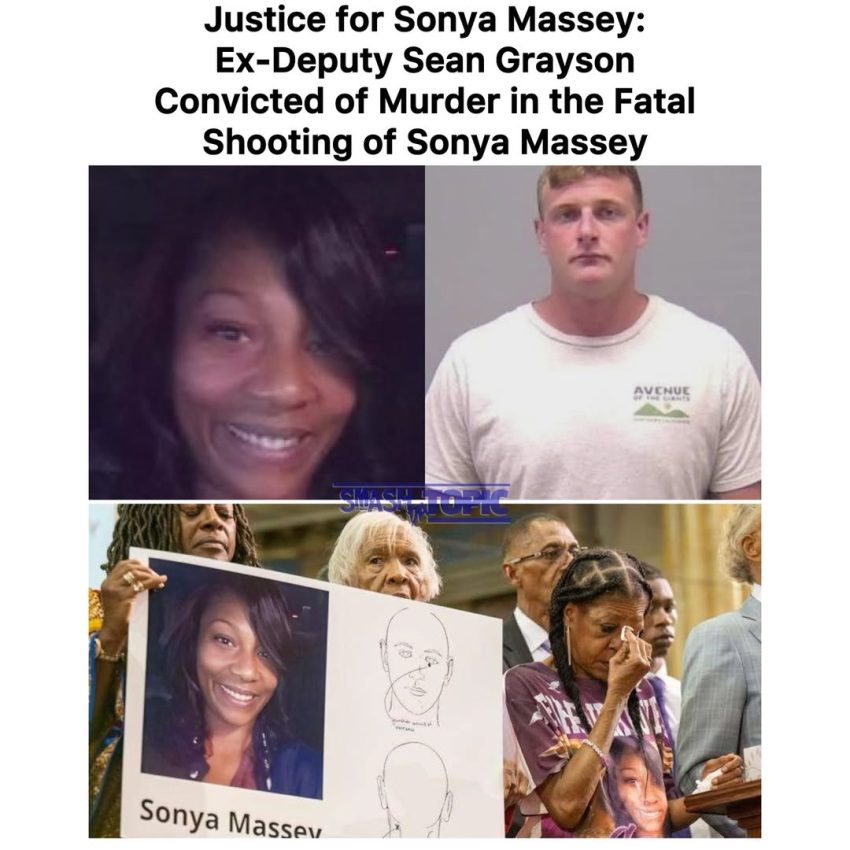

On October 29, 2025, a Peoria, Illinois jury delivered a verdict that echoed far beyond the courtroom: former Sangamon County Deputy Sean Grayson was found guilty of second-degree murder in the killing of Sonya Massey, a 36‑year‑old Black mother who had called 911 for help from her own home. The case, marked by chilling body‑camera footage and fierce debates over mental health response, has become a stark example of the frailty of trust between citizens and those sworn to protect them.

Massey made that fateful call on July 6, 2024, from her home in Woodside Township near Springfield, reporting what she believed was a prowler outside. When deputies arrived, the situation unraveled in her kitchen. Body‑camera footage—principally from Deputy Dawson Farley’s camera—showed Massey retrieving a pot of hot water, pleading “Don’t hurt me,” repeating “Please God,” and at one moment saying, “I rebuke you in the name of Jesus.” Grayson later claimed he believed Massey intended to throw the water, perceiving a threat. The jury ultimately sided with prosecutors who painted the event not as a split‑second error but as a tragic overreaction.

Grayson entered the trial facing three counts of first‑degree murder, alongside charges of aggravated battery and official misconduct. Though the jury did not convict him on first‑degree murder—charges that would have carried 45 years to life—they found him guilty on the lesser, but still serious, count of second‑degree murder. His sentencing is set for January 29, 2026, where he could face 4 to 20 years behind bars—or, under certain interpretations, probation.

In court, the trial unspooled in raw, painful detail. Prosecutors showed video of Massey standing near the stove as deputies shouted commands to “drop the pot.” They underscored that much of Grayson’s own body camera record wasn’t activated until after the shooting—raising doubt about his narrative. Defense attorneys countered that Grayson believed he faced mortal danger. He testified that Massey’s rebuke felt like an attack, that the water pot was dangerous, and that he feared the Taser would fail. Farley, the other deputy on the scene, testified that Massey never made moves to harm officers; he did not fire his weapon.

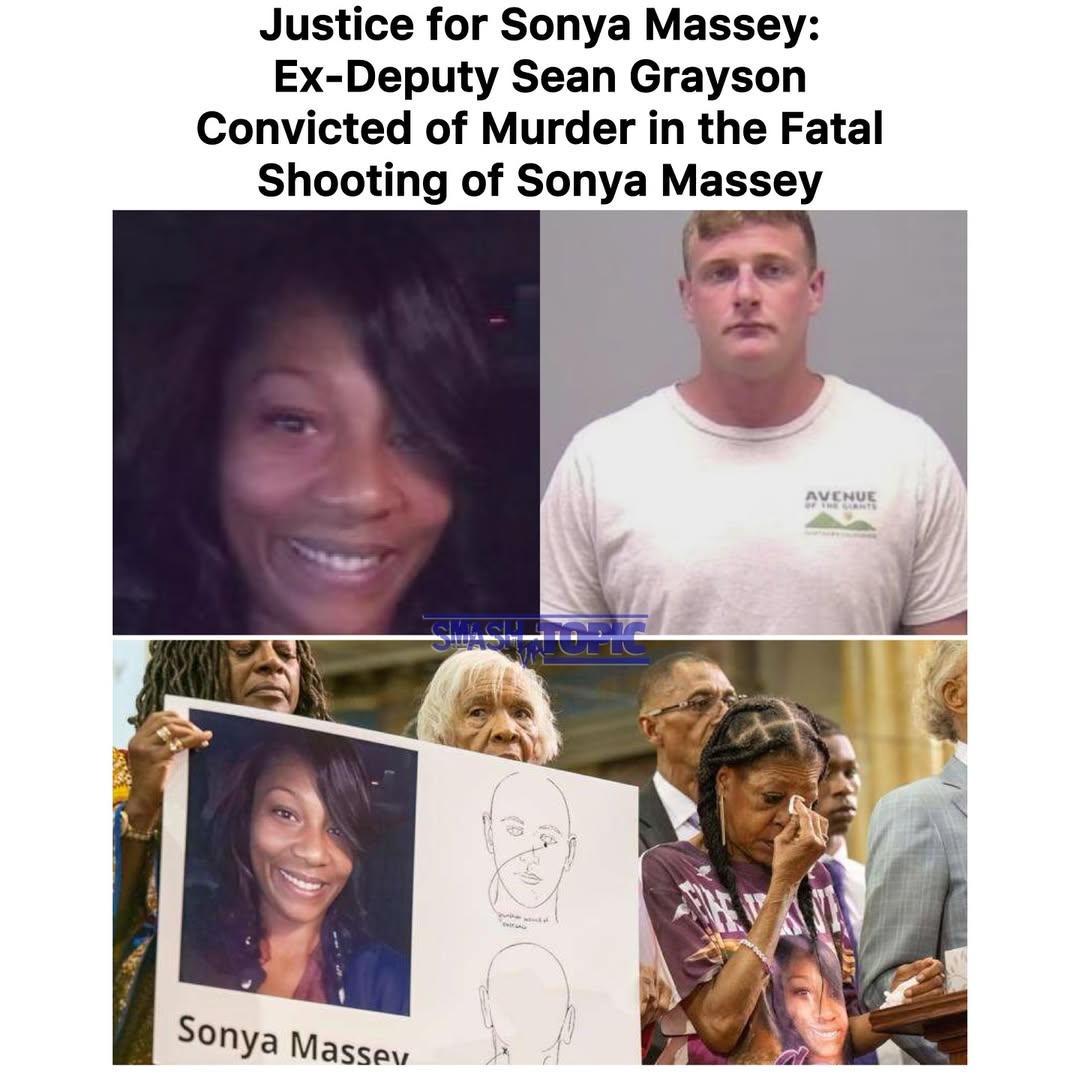

Beyond the courtroom, this case stirred widespread outrage and calls for reform. Local leaders and civil rights advocates pushed for changes in policing, including stricter screening for law enforcement hires, better mental‑health crisis protocols, and accountability for officers. In February 2025, Massey’s family secured a $10 million settlement from Sangamon County—though they maintained that civil recompense cannot replace criminal accountability.

Massey’s father, James Wilburn, responded to the jury’s verdict with anguish and frustration, calling it a “miscarriage of justice” because, in his view, his daughter had been murdered in her own home. Civil rights attorneys Ben Crump and Antonio Romanucci, who represented the family, noted that the decision “is still a measure of justice,” while pushing for a “meaningful sentence” and systemwide changes.

For the Massey family and for many watching across the country, Wednesday’s verdict may feel like both progress and heartbreak. Grayson’s conviction marks accountability—though not to the full extent sought. In the weeks ahead, all eyes will be on the judge’s sentencing decision in January, and whether this case becomes a turning point for how law enforcement handles mental‑health crises in Black homes.